Dionís Bennàssar (1904 - 1967) - Capturing Pollensa's Spirit amid a Changing Era

Dionís Bennàssar (1904-1967), born to a humble peasant family in Pollença, Mallorca, rose from rural roots to become one of the island’s most celebrated artists.

A restless talent, he showed an early gift for drawing, balancing fieldwork with sketching. After studying in Palma while working as an electrician, he returned to Pollença, where the 1920s art scene shaped his style. A gunshot wound forced him to relearn painting with his left hand, a testament to his unyielding drive.

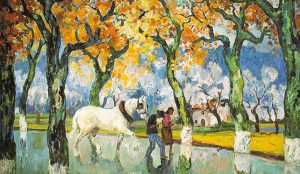

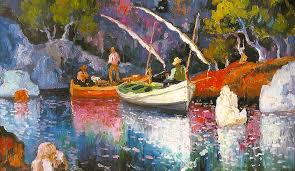

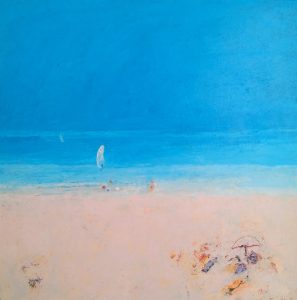

Bennàssar’s mastery in capturing Mallorca’s luminous landscapes-vibrant colors and post-impressionist brushstrokes-earned him acclaim as a leading landscape painter. His works, exhibited across Mallorca, Madrid, and Valencia, opened new paths in painting, blending quick perception with deep emotional resonance. A grant from the Balearic Islands’ Provincial Council fueled his studies in Spain’s major cities.

His Pollença home, now the Museu Dionís Bennàssar, preserves his legacy, hosting exhibitions and community events in a 17th-century house. Surrounded by the UNESCO Serra de Tramuntana and beaches like Formentor, Bennàssar’s art reflects Mallorca’s soul, making him a cultural icon.

Read in-depth chapters of his biography below

At the turn of the 20th century, Pollença, a town set against the majestic backdrop of the Serra de Tramuntana, began to experience significant cultural shifts. Its raw, untouched beauty and unique quality of light captivated artists and intellectuals from across Europe and beyond. Catalan modernist painters like Hermen Anglada-Camarasa, Joaquim Mir, and Santiago Rusiñol were particularly drawn to Mallorca, establishing what became known as the “Pollensa School”. Their presence marked a turning point, stirring the tranquil waters of traditional Mallorcan life.

This artistic arrival marked the birth of Mallorca’s tourism, and coincided with the development of Hotel Illa d’Or and Hotel Formentor (now owned by Four Seasons), the latter founded by Argentine millionaire and patron of the arts, Adán Diehl in 1929. Both hotels were conceived as cultural meeting points for artists and literati, and quickly became magnets for creative individuals and global elites, hosting luminaries such as Winston Churchill, Agatha Christie, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Jorge Luis Borges, Charlie Chaplin and Robert Graves. These distinguished visitors, arriving via motorship or early airplanes, transformed a secluded part of the island into a vibrant international hub.

However, this emerging cosmopolitanism stood in stark contrast to the deeply traditional and often isolated rural society of Pollença, particularly during the subsequent Franco dictatorship. Daily life for most locals revolved around agriculture, with horse-drawn carts common on unpaved streets until the 1960s. Basic amenities were slow to arrive; fresh water was typically drawn from wells, and modern conveniences were a luxury.

Within this evolving context lived Dionís Bennàssar, a native Pollença painter whose life uniquely bridged these contrasting worlds. With an insatiable appetite for the modern world and a fierce drive to connect with these new visitors, he forged a remarkable path—yet not without overcoming the shadows of a turbulent youth that shaped his extraordinary journey…

Dionís Bennàssar’s journey began not with privilege, but with early loss and the quiet strength born of necessity. Born on the 3rd April 1904, his childhood unfolded during a time of limited opportunities, setting the stage for the determined pursuit of his artistic passion later in life.

Young Dionís Bennàssar’s life was marked by early loss, as both his mother and father passed away when he was a child. The responsibility for the younger siblings fell largely to his older sister, Francisca, who never married. She became a central figure in their lives, caring for them while supporting herself by working as a seamstress, sewing shirts.

Formal education was brief for Dionís. He stopped attending school at the age of seven, right after his first communion. With schooling behind him, he was sent to work guarding pigs. Even amidst the practical demands of his youth, a different kind of calling stirred within him. Before his military service, Dionís showed an interest in art and travelled to Palma to take drawing classes.

However, this promising start was abruptly cut short. He was expelled from these classes. It is understood that this unexpected turn may have been connected to his brother, who was studying to become a priest in Palma. In that era, the state and church were closely intertwined, exerting significant control over various aspects of life, including education. When Dionís visited his brother in Palma, it seems this visit somehow led to authorities reportedly telling him not to return to the drawing classes, potentially as a way to encourage him to leave the city and cease his studies, which were possibly state-funded. The power of the church at the time, even influencing private matters, could also have played a role. Tragically, his brother later died of meningitis.

Before his military service, Dionis pieced together a living through various small jobs, such as a mechanic, but none developed into a stable, professional career. During this period, he did paint a little, but it was described as very minimal and purely as an amateur, done out of personal interest rather than professional intent.

These early years, marked by profound personal loss, limited schooling, and the hustle of varied small jobs, painted a picture of a challenging yet formative childhood.

Such experiences, however, cultivated a resilience that proved crucial in navigating future conflicts and political turmoil, reinforcing his quiet determination to dedicate his life to the art he loved.

Dionís Bennàssar’s early adult life was marked by a defining experience: his participation in the Rif War, also known as the Moroccan War.

A young man from a poor family with seven siblings, Dionís volunteered for military service around the age of 20, departing Pollença for North Africa.

Life as a Spanish soldier in the Rif War was often impoverished and grueling. Spanish forces in Morocco were largely comprised of conscripts and reservists from the poorest elements of Spanish society, many of whom were illiterate and had minimal training. They were poorly supplied and prepared, with reports of widespread corruption among the officer corps leading to reduced supplies and low morale. Soldiers received a meager pay, roughly equivalent to thirty-four US cents per day in 1921, and lived on a simple diet, often resorting to bartering their rifles and ammunition for fresh vegetables in local markets. Barracks were unsanitary, medical care was poor, and outposts in the mountains (known as blocaos) often lacked basic sanitation, leaving soldiers exposed to both enemy fire and diseases like malaria and typhus, which could be a virtual death sentence.

It was during this conflict that Dionís sustained a severe injury, a gunshot wound to his right collarbone (clavicle). The immediate aftermath involved a gruelling operation lasting five hours, followed by a six-month recovery period in a hospital in Larache, Morocco.

This injury had a lasting impact. Although his right arm eventually recovered some strength over the years, he noted that it did not have the same strength as before, with the muscle in his clavicle being severely damaged. Critically, this physical limitation compelled him to relearn his craft, painting primarily with his left hand. While he could still write with his right hand, it quickly caused fatigue. As a recognized war invalid (inválido de guerra), Dionís received a very small military pension for the rest of his life. This modest income, supplemented by daily military bread rations, known as chuscos, which were provided for many years, provided a basic existence that afforded him the freedom to dedicate himself to painting.

He returned from the war with no clear prospects for a conventional career, but this small, consistent income became his unique path to an artistic life.

Returning from the Rif War severely wounded by a gunshot, Dionís Bennàssar had to relearn his craft, adapting to paint with his left hand due to lasting damage to his right arm. This challenging period, supported by a modest military pension and daily bread rations as a war invalid, marked the true start of his dedicated artistic journey.

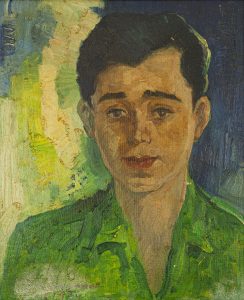

In these early artistic days, Dionís, still a young man, was actively exploring and experimenting with various styles and techniques. His initial works did not yet possess the distinct personality or refined technique that would characterise his later pieces. For instance, he often did not paint faces in his early works. He also demonstrated an openness to experimentation, frequently retouching earlier drawings with new pens or inks, sometimes dating them years after their original creation, indicating a playful disregard for strict chronology in favor of continued artistic exploration.

However, amongst this exploration, Dionís was given his first exhibition in Palma in 1934, where he received critical acclaim as an introducer of modern painting in Mallorca. While sometimes associated with the “Escola Pollencina” (Pollensa School) of painting, he was also celebrated for his essential originality and constant artistic exploration, and the success of the exhibition established him as an artist distinguished from other Mallorcan artists of the time, many of whom had stronger tendencies to imitate popular styles.

His boundless curiosity, fueling his restless creative spirit, profoundly shaped his artistic and expressive choices, drawing him to global culture and technology.

In stark contrast to the traditional and often closed way of life in Pollença at the time, he possessed a deep interest in looking beyond Mallorca’s borders and engaging with the wider world. He meticulously studied foreign publications like Life, Selecciones (Reader’s Digest), and National Geographic, absorbing information primarily through their vivid images, even with limited English proficiency. He actively sought out and befriended foreign visitors – artists, intellectuals, and elites drawn to the island to gain insights from beyond Spain’s borders. His home in Pollença transformed into a vibrant intellectual hub, serving as a bridge between the international and local worlds where discussions spanned a wide array of topics, from art and culture to pressing global events.

This outward gaze profoundly shaped both his artistic and personal life. His foreign friends, understanding his passion, often brought him gifts of cutting-edge art supplies and technologies unavailable in Spain. This unique blending of his technical curiosity with his artistic drive infused his work with a truly cosmopolitan edge, distinct from traditional local artistic norms.

Under Franco’s oppressive censorship, Dionís’s lifelong ties with foreign friends and likeminded thinkers gained dangerous weight. Viewing the dictatorship as an enemy, his disregard for religious norms, including rarely going to church, was a notable stance. His tertulias turned into clandestine lifelines, fueled by a Swedish transistor radio—gifted by a foreign friend—that brought suppressed global news. Friends, some imprisoned for their left-wing views, gathered to listen and discuss, quietly hoping for Franco’s fall

It was precisely this openness and refusal to conform that placed him in grave danger, as his outward-looking view and the candid discussions within his home almost cost him his life….

During the turbulent initial months of the Spanish Civil War, a period rife with personal vendettas within towns, Dionís faced a terrifying ordeal: an attempted execution. In 1936, he was detained by local individuals from Pollença—not official military personnel—and taken to Monte Sión, the site of the current town hall. There, his captors subjected him to a simulated execution, firing shots into the air instead of at him. This chilling experience was, in Dionis’s words, designed to “destroy him morally”.

Dionís was spared by an ironic twist of fate. Franco had enacted a law stating that military personnel had to be judged by military tribunals, not by civilians. As a recognized war invalid (inválido de guerra) and former corporal (cabo) from the earlier Rif War, Dionís was technically under military jurisdiction, a legal loophole that saved his life.

Following this terrifying simulated execution, Dionís fled to the countryside, seeking refuge for an unspecified time at the house of his brother-in-law Juan, a miller, who offered a safe haven to wait out the war’s most perilous phase. This retreat was a calculated move to escape the village’s volatile political tensions.

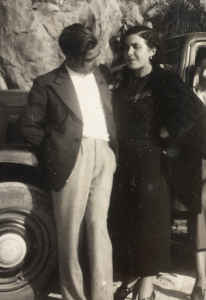

While Dionís was in refuge he maintained a correspondence with his girlfriend, Catalina Vicens Vives, who would later become his wife. She had moved to Palma to live with friends during this period. Their relationship, already established as a couple, continued through letters.

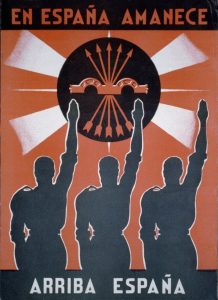

Upon his return from refuge, Dionís faced another direct confrontation with the regime. He was forced to affiliate himself with a pro-Franco party. Given the choice between the Falange and the Requetés, both factions of Franco’s supporters, he hesitated. He was beaten and compelled to sign up with the Falange.

This coerced signing, however, was merely a formality; he never actively participated in any of their activities. This brutal act underscored the regime’s oppressive tactics, aimed at breaking the spirit of its perceived opponents and enforcing outward conformity.

Yet, even in this dark chapter of fear and coercion, the seeds of a wonderful transformation were taking root; a new phase of his life where he would build a family with Catalina, and further embrace his experimental artistic vision to forge the distinctive style that would cement his enduring legacy.

This selection of Dionís Bennàssar’s autobiographical account captures the anguish, fear, and powerlessness that marked one of the saddest, most harrowing, and bloodiest episodes in contemporary Spanish history: the Civil War.

His words, written with caution and a sense of fear, offer a vivid glimpse into the turbulent events of July 1936 in Pollença. Bennàssar notes with restraint, “it falls to Pollença’s history to describe the mentioned events with greater clarity.”

July 1936: Seville announces, in clear words under the banner of the Republic, an anti-government military uprising led by Franco, joined by Falangists of J.A. Primo de Rivera and Catholic Requetés of the Monarchist Party.

July 19: Military forces seize the Pollença Town Hall under gunfire. People have a bad feeling. A local has died.

July 24: Men and women are constantly detained; the prison is full, and the most dangerous are taken and distributed to prisons in Palma. Panic is widespread. The cry of “Arriba España” is mandatory as the war’s slogan. These are moments of anguish and confusion. A few control the population, poorly advised by the biggest smuggler. They even took revenge on the children. Despite ordering others to do things, they were the only ones responsible for many innocent deaths and over three hundred civilian prisoners. Nighttime executions, scattered along Mallorca’s roads, imposed by Mussolini’s Italian fascists, are in full swing. I am shaken, and nothing weighs on my conscience.

August 23: At ten in the evening, I was surprised inside a bar—Bar Alhambra—and taken by armed civilians to the Town Hall. I am locked up there, and the two men in charge of guarding me have bad reputations; one is a known thief, and the other shot himself in the finger to avoid military service. At three in the afternoon, in the porch, with my face to the wall, I endured a mock execution, an attempt to humiliate my personal dignity.

January 3, 1937: I try to escape all commitments and take refuge where my brother-in-law lives, at the Ca’n Xura mill in Pollença’s Horta. I live without friends. There is neither war nor peace. The trees and walls have ears. Everything and everyone breathes fear.”

Dionís Bennàssar’s unique artistic journey was deeply intertwined with his personal experiences, particularly his courtship during the tumultuous late 1930s. This period of his life coincided with a significant phase in the forging of his distinctive artistic style.

Courting Amidst Turmoil (Late 1930s)

During the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), Dionís was in a relationship with Catalina Vicenç Vives (born 1906), who would later become his wife in 1943. This challenging period saw Dionís taking refuge at his brother-in-law Juan’s mill in Canjura, in the Pollença countryside, to avoid the dangers and complications of the war.

While he was there, Catalina went to live with friends in Palma. Their relationship continued through letters, and one painting, dated 1936-37, theoretically depicts Dionís reading a letter from his girlfriend in Palma. These paintings from Canjura are regarded as his most interesting works from this period. They include scenes of typical Mallorcan life, such as people returning from work with carts, a common sight in Pollença until the 1960s.

Forging a Distinguished Artistic Style

Even amidst the personal and societal upheaval of the late 1930s, Dionís was actively painting and developing the style for which he would become distinguished. His artistic output from his time in Canjura showcases his evolving technique. He became recognised for his exceptional sensibility for beauty, for composition, and for the sense of color.

Dionís had already made his public debut in the art world prior to this, with his first exhibition taking place in 1934 at the Galeries Costa in Palma. This exhibition earned him critical acclaim, with some critics hailing him as the introducer of modern painting in Mallorca.

Regarding a 1940 Exhibition, Tito Cittadini, the prominent Argentine painter, who presented the event, said of him: “His art is more than rhetoric; it is sensibility, pulsating, beauty, in the aristocratic sense of the word…”

Dionís held a profound appreciation for what he described as “The Power of Color”. Around this period, through blending a post-impressionist approach with a deeply personal response to his homeland, he began creating works that resonated with emotional and vibrant imaginative power, significantly contributing to a redefining of Mallorcan painting.

Dionís’s color application was also informed by his engagement with color theory, likely influenced indirectly through his modernist contemporaries. While he did not explicitly reference scientific color theories like those of Michel-Eugène Chevreul (who explored simultaneous contrasts), his intuitive use of complementary and harmonious colors created dynamic visual effects that align with early 20th-century experiments in color perception. His ability to make colors pulse and vibrate suggests a modernist fascination with color as a source of energy and movement.

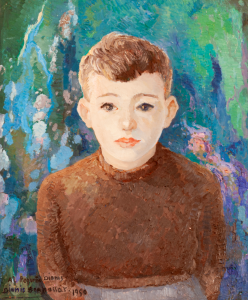

His son, Toni, later opined that his father’s active use of bold, cheerful colors in his art may have simply been a way to symbolically counteract the difficult life which he had endured up until this period.

Dionís Bennàssar’s studio, preserved at the museum house, was the beating heart of his artistic and family life. In 1943, Dionís purchased the property and married local pianist Catalina Vicenç Vives, known as “Moreta.”

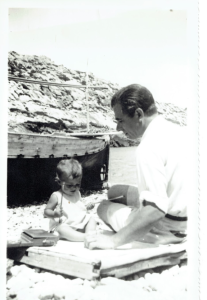

The following year, in 1944, their only son, Toni, was born through a complicated birth which meant Catalina could not have more children.

Over time as his young son grew, this space became a a place of family inspiration where Dionís’s unique approach to art was not only practiced but shared with Toni, turning daily interactions into profound discussions on art and life.

Toni Bennàssar recalls having constant access to his father’s studio and observing the ongoing creative process.

Dionís developed a distinctive painting style characterized by sincerity, authenticity, and vibrant spontaneity. His method was relatively quick and direct, applying paint straight to the canvas without waiting for layers to dry. His passion for creation was almost an obsession, a mania for painting everything that was put in front of him. This included everyday objects within the studio and home, such as his clock, windowpanes, and even furniture.

In the company of his son, Dionís would paint aloud as he worked. He would meticulously explain his techniques and the rationale behind his color choices to his son, even though Toni aspired to be a musician, not a painter. He would clarify why he chose a specific color to create contrast with another. Toni later recalled how he would often emphasise the importance of originality and authenticity, contrasting it with what he understood as vulgarities. He taught about the unity of the painting, explaining the methods to how he composed his works so that all elements would draw the viewer’s eye inward. He also discussed subjects on the richness of forms and composition, Toni recalling a specific conversation about the expression of a line. These were not just artistic concepts but reflections of his broader philosophy, encouraging his son to “live nobly, what we are”.

One story concerns a painting of a “noria” (waterwheel), which his uncle considered one of his best cuadros. While in his studio, Dionís was painting a new work on the easel. However, an older painting, depicting the waterwheel, lay discarded directly on the floor. Whilst Dionís was working on his new piece, he walked back and forth over this previously created canvas, as if completely oblivious to it.

When asked by his brother why he was stepping on the painting, Dionís simply stated, “No me gusta” (I don’t like it). He then casually offered it to his brother, saying, “If you want, you can take it”. The story suggests his complete disregard for a completed work once his personal sentiment towards it changed, even if others highly valued it. This particular painting, documented in a book and slides, is believed to still be with his uncle’s family.

As previously mentioned, Dionís Bennàssar’s character was profoundly shaped by his fascination with progress and new technologies. He consistently sought out and embraced new innovations, often being among the first in Pollença to acquire them for his home. This keen interest in what was new and advanced was a constant theme throughout his life.

He was notably an early adopter of several modern conveniences in Pollença, reflecting his enthusiasm for technology:

He installed one of the first private well water pump in Pollensa at his house around 1945-1950, providing running water when many in the village still relied on public taps.

He owned the first Vespa in Pollença.

He was among the first to acquire a refrigerator in the mid-1950s.

As previously mentioned, he possessed one of Pollença’s first powerful long distance transistor radios, imported from Sweden, which allowed him to tune into international broadcasts that were otherwise inaccessible due to Francoist censorship.

One of the most notable examples of his technological pioneering was the acquisition of his butane gas stove. This stove was brought from Italy around 1960 by friends from the military base at Puerto Pollença, including General Lorente, whom Dionís knew because they painted together. The remarkable aspect of this acquisition was that butane gas itself was not yet available in Spain. For a couple of years, his wife enjoyed the gift of the modern stove but no gas to cook with. When butane finally became available, the novelty of the stove was such that the local appliance salesman would bring his potential customers to Dionís’s home every day to demonstrate how the new butane kitchen worked. This made their home a temporary exhibition space for emerging household technology.

While the artistry of Dionís Bennàssar is celebrated within these walls, it is equally important to illuminate the life of Catalina Vicenç Vives, his wife, affectionately known as Catalina “Moreta.” Born in Pollença in 1906, Catalina was a woman of remarkable talent and resilience whose personality and presence profoundly influenced Dionís and shaped their family life.

Early Life and Musical Prowess

Catalina’s nickname, “Moreta,” originated from her father Jaume Vicenç’s carpentry shop, “cal Moret,” which had once employed a young Moor. Her father was not only a carpenter but also a clarinetist and director of the Pollença Music Band. Growing up surrounded by music, Catalina began studying piano at a very young age, as women were not permitted to play wind instruments at the time. Her father was a strict teacher, demanding hours of practice and imposing severe punishments for mistakes. Despite their humble background as carpenters, the family acquired a piano, and Catalina’s lessons were reportedly given by Mrs. Mossgraber, the wife of a German painter, highlighting the significant influence of foreigners in Pollença.

Catalina quickly demonstrated extraordinary musical aptitude and managed to earn a living through her musical talents:

Silent Film Accompanist: Catalina captivated audiences by improvising music for silent films at the Can Franc cinema in Pollença’s Plaça Vella. She would match the mood of the projected images – be it animated, sad, romantic, or comical – with her spontaneous piano playing. This fascinating period of her life ended with the advent of sound cinema, an event she later recalled with joy.

Pollença Jazz Band Member: She also played with the Pollença Jazz Band, an “orchestra” that included her uncle Guillem Cladera “Punxa” and her father’s friend Martí Campomar “Vage”. The band achieved considerable popularity, playing international music (mostly North American) from scores obtained in Barcelona. They toured extensively around Mallorca, performing at local festivals in places like Llucmajor and Sa Pobla, and were often re-hired for the following year due to their success. They also performed for foreign visitors in hotels, bars, and chalets, such as the Hotel Formentor and Hotel Illa d’Or, earning a good income, sometimes equivalent to a stonemason’s weekly wage.

Absolute Pitch: Musicians who knew her later suggested that Catalina possessed “absolute pitch,” a rare ability to identify any musical note by ear without external reference. This explains why she could correct her son Tony’s flute playing from the kitchen. It also made her critical of other musical groups, like the Pollença Music Band, which she found constantly out of tune. Nevertheless, she enjoyed attending concerts at the Pollença Festival, capable of mentally transcribing every note she heard. Her strong character, described as “decided and mischievous,” occasionally led to friction within the orchestra, with one anecdote suggesting that her departure brought “peace to the orchestra”.

Marriage and Family Life

Catalina married Dionís Bennàssar in 1943. Their union meant that the Pollença Jazz Band rehearsals transitioned to their new home, here, at Carrer de la Roca number 14. Their house featured a “piano room” where Catalina’s piano was kept, and where their son, Toni, later studied music.

Her musical career largely concluded when she became pregnant with her only son, Toni, in 1944. As was customary for women of her time, she left the orchestra to become a dedicated mother and wife, focusing on the household.

Influence on Dionís and Place in the Family

Catalina was a fundamental influence on him. Her face was frequently recognisable in the female figures and nudes he painted, even when they were not direct portraits. He often painted her from memory, particularly in his later years, even without her posing.

Within the family, Catalina was the anchor, managing the practicalities of daily life. Her father also lived with them in the piano room for about ten years after his wife died, demonstrating Catalina’s central role in caring for her family.

Later Life and Enduring Legacy

Dionís passed away suddenly from a heart attack in 1967 at the age of 63. Catalina continued to live in their home, and for years, she and their son Toni cared for each other. Later in life, she developed a neurodegenerative disease, similar to Alzheimer’s, which gradually diminished her mental and physical faculties. Despite this, she remarkably continued to play the piano. After her death, her piano was sold by Toni, as it was an old, out-of-tune instrument. Though he later regretted it, and years later he sought out the owner, bought it back, and placed the piano back in its original place within the house, which visitors can now see.

Catalina “Moreta” Vicenç Vives, though less publicly recognised than her artist husband, was an artist in her own right, particularly through her exceptional musical talent. Her story exemplifies the lives of many women of her era, whose potential was often constrained by societal expectations, yet who found ways to express their creativity and profoundly impact their families and communities. Her enduring presence in Dionís’s art and their home stands as a testament to her quiet yet powerful significance.

A small room on the stairs at the museum house holds a profound connection to the life and legacy of Dionís Bennàssar, and equally, to his son, Antoni “Toni” Bennàssar Vicenç. For many years, this room served as Toni’s private sanctuary and creative refuge, a testament to a childhood spent immersed in a unique blend of artistic passion, technological pioneering, and enduring family bonds.

Though Toni initially aspired to be a musician, his father nevertheless encouraged his early attempts at painting, correcting his works, with the intention not to discourage but to teach. Toni recalls their bond as one of close friendship rather than formal parenthood, always addressing his father as the informal “tú” (you), in contrast to the more respectful third person”vos” or “papá/mon père” used by some of his friends for their parents.

His childhood memories are filled with everyday joys and the unique aspects of their home. The patios and terraces were Toni’s primary play areas, where he and his friends would stage elaborate games, sometimes based on movies they’d seen, transforming the space into a boxing ring or an Indian camp. He remembers the old wood-burning stove where water was heated for laundry, though they rarely used it for warmth, preferring a portable brazier. The family raised a goat for milk, which was kept in the courtyard.

Toni’s Artistic Path and the Foundation’s Vision

Toni Bennàssar’s own artistic journey reflects the rich environment he grew up in. Initially, fulfilling his ambition to follow his mother’s path, he pursued a career as a musician, playing in bands that toured the Mallorcan hotels, but his life took a pivotal turn in 1967 when his father died suddenly of a heart attack at age 63, when Toni was just 23.

In the years following, Toni picked up the brush, and over time began to cultivate his own distinct expressionist nuances. His work primarily features the stunning mountainous and marine landscapes of Mallorca, and by the 1990’s he had gained significant recognition, exhibiting successfully in Madrid, Sweden, and Germany.

It was Toni who spearheaded the creation of the Fundación Dionís Bennàssar, housed in their ancestral home.

Inaugurated in 1999, the foundation’s mission is to exhibit, catalog, conserve, and promote Dionís’s work and philosophy, the latter through fostering community engagement by providing a space for creative and intellectual events, and serving as a cultural bridge that brings international talent to Pollença through inspiring conferences and workshops.

The Dionís Bennàssar Foundation stands as a vibrant testament to the artistic brilliance and pioneering spirit of Dionís Bennàssar, while also honoring the enduring support of his family—his talented and devoted wife, Catalina Vicens, and their son, Toni Bennàssar Vicens, whose steadfast commitment has sustained this legacy.

Rooted in the inspiration of family, the foundation continues to thrive, now guided by Toni’s daughters, who carry forward this rich heritage with passion and dedication.